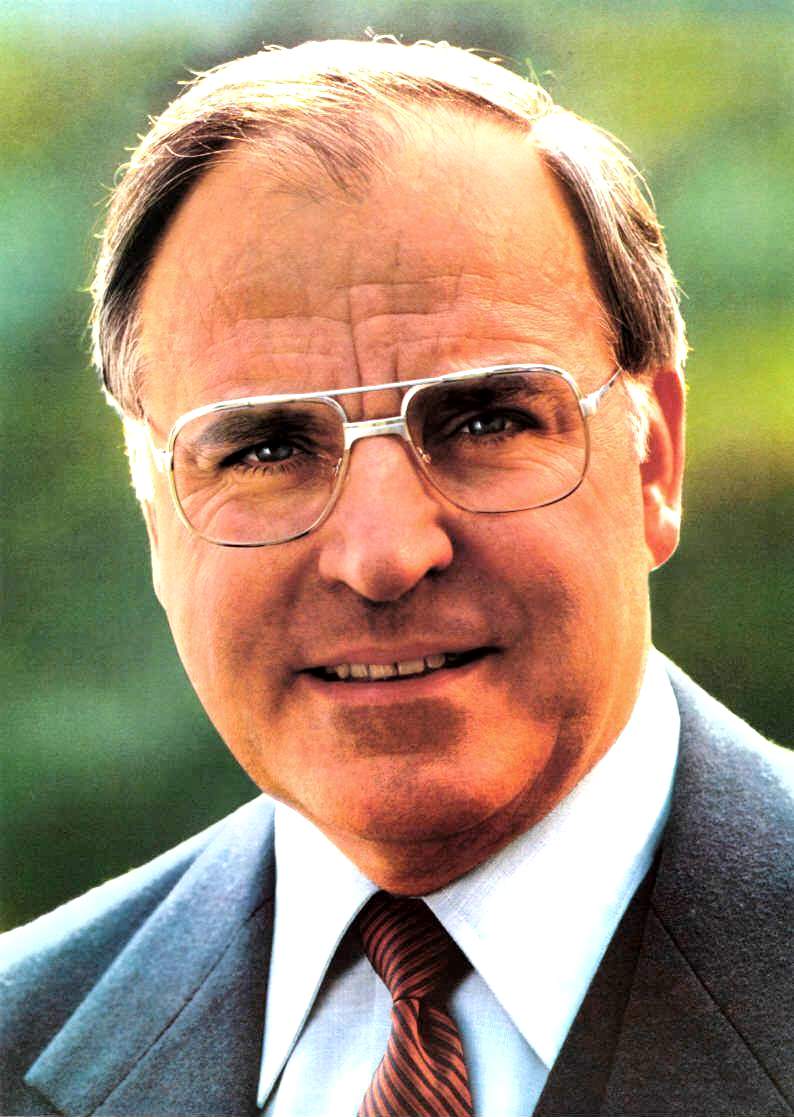

THE DEFACT OF RE HELMUT

BERLIN – IS A STRONGER VOTE, more severe than expected, the one with which the Germans fired Helmut Kohl. A vow that denies the old chancellor the right to officiate the epilogue of the two great enterprises realized in the sixteen years of uninterrupted power: the return of the capital to Berlin, final touch to reunification; and the birth of the euro, which he wanted despite the reluctant country. On his face there was a more contrite bitter expression, last night, while he was responsible for the defeat, and announced his withdrawal from the presidency of the party. The most deserving chancellor, in the eyes of Europeans, received from Germany the heaviest punishment ever reserved for a chancellor in the history of the Federal Republic. No one else, in fact, before him, had been kicked out with a vote for universal suffrage. Cruelty and wisdom can overlap, mingle, in the popular will. It is in fact not guaranteed that the victorious general on the field is then the most suitable to manage the victory. By electing Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder, who was skeptical about the opportunity for too rapid reunification, and the same about the rhythms imposed on the birth of the euro, the Germans have perhaps made the brisk sunset of Kohl even more humiliating. But Schroeder, long since converted to the single currency (and obviously to the reunification), will be able to manage the two big businesses of the old chancellor with an energy and effectiveness that their creator perhaps no longer had. And even without the indulgence of those who follow the growth of their creatures. It is very likely that the Germans thought of this in deciding a turn, whose meaning is not historical only for Germany. The turning point is European, as well as German, because yesterday Germany decided to abandon its past to history. This is perhaps the deepest meaning of the election of Gerhard Schroeder and the sunset of Helmut Kohl. Germany has not thrown its past. He entrusted it to textbooks. He decided not to take it with him in the next century. Neither in Berlin, in the capital that will meet again in spring, after more than fifty years. That past must no longer weigh on his present actions. This can change the nature of its relations with Europe. In the memory of the new chancellor there are no images of World War II: the images, the direct memories that accompanied Kohl, will not influence his behavior.

Schroeder is for united Europe because it is German; not because his German memory makes him feel guilty with other Europeans, and therefore in duty to give them a piece of national sovereignty in pledge. For example the mark. That understanding, if not just surrender, that Kohl’s indulgence for the upsurge, the French whims, or the Italian weaknesses, was partly due to that state of mind. To the teaching received by Konrad Adenauer. His attitude contributed to making it pleasing to Europeans. In the successor there are no longer those guilt complexes. There will be none in the baggage of the government that in ’99 will move from the Rhine to the Spree. The young Germans, who like Schroeder do not have a direct memory of the obsessive national past, they wanted to free. They left with Kohl. Does Europe have to regret it? I do not believe. An adult Germany, with political responsibilities appropriate to its economic weight, is a step forward also for the European Union. Only a conservative neurosis (or hysteria) can lead one to see in Gerhard Schroeder a danger, a pitfall, for the process of European integration. Or worse still, a symptom of nationalism that resurrects, as soon as Kohl’s Europeanist veil has been dissipated. Sure, Schroeder does not speak as the philosopher Jurgen Habermas, his supporter, who considers constitutional patriotism as the only licit and modern form of national sentiment. He, Schroeder, insists on German interests. It will be necessary to learn that the latter, when they are discussed, do not amount to a threat from the past. In concrete terms, at European level, unlike Kohl, Schroeder has declared himself in favor of a common policy aimed at combating unemployment. As for the European Central Bank, he seems close to the French thesis, according to which a political counterweight should be created. With the social democrat Schroeder appear on the political scene, in the front row, also Christian Democrats of the same generation. That of ’68. I refer to the successors of Kohl. First of all to Wolfgang Schaueble, the most popular German politician, the official dolphin of the defeated Chancellor. And also to his party partner Volker Ruehe, minister of defense in the government that leaves. Like Schroeder, both Schaueble and Ruehe have a clear memory of the direct images of Nazi horrors. And like the new chancellor they have no complexes, they are not afraid to talk about German interests. Not even Schaueble and Ruehe want to transfer the past (so much present in Kohl) to the rebuilt Berlin and the new capital of united Germany. Gerhard Schroeder did not rule out the possibility of a Grand Coalition.

Yesterday’s vote marked without any doubt a sharp turn to the left. The voters gave the new chancellor the necessary majority to form a red-green government, that is, with Social Democrats and Greens. But Schroeder said he will study all the possible formulas. Even that, in fact, of a Great Coalition, with the Christian Democrats defeated. However, the latter rejected the hypothesis. The defeat was still hot. The counting of votes was under way. It was difficult for Theo Waigel, a close Bavarian ally of Kohl, to say that he was ready to live with the winners. It would not have been dignified. Neither Schroeder can attempt that path before starting negotiations with his natural allies, the Greens. that’s what will happen in the next few hours. But are the Greens, the ideal allies for Gerhard Schroeder? Joschka Fischer, their leader, could be an excellent vice chancellor and foreign minister. Tradition has it that this charge is reserved for the second party of the ruling coalition. Former sixty-eight, a friend of Cohn-Bendit, Fischer has repeatedly expressed his ideas on what must be German foreign policy. What will happen after Kohl? he asked himself. “The answer is simple: a more powerful Germany will remain faithful to its European vocation, because its interests, its history, its obligations invite it to this”. Fischer has dealt intelligently with the aspects of the eternal German question.

Reunified Germany has once again become central power on the Old Continent, like it or not by its neighbors. How to use this power? The objective data, the strategic potential of the country, the geopolitical situation, are not the only ones to have a decisive weight. The terrifying history of the ‘900 makes subjective factors intervene. In any case, they expose German foreign policy to criticism. If Germany refuses to assume its responsibilities, it is accused of being too Swiss. If on the contrary, it assumes them, it raises atavistic fears. The only solution is European integration. It is a wisdom to Kohl. But Fischer’s clarity of purpose is not shared by the base of his party. On some crucial issues it remains divided. It is on the Bundeswehr’s military interventions in the framework of the UN peacekeeping operations. It is about participation in NATO. And there is no shortage of those who want sudden increases in fuel prices, or wish for extravagant or unattainable ecological initiatives. Others are ideal partners for Schroeder. They must be less unpredictable. The Grand Coalition would allow him to maintain the promised stability, to remain faithful to the electoral slogan that has been so successful: “Do not change, but do better”. For this reason the ideal allies would be the successors of Kohl: Wolfgang Schaueble and Volker Ruehe. Their participation would assure the restless industrialists, the business world and, not so paradoxically, mitigate the pressures of the Social Democratic party, ready to curb the overly-pragmaticism of the new chancellor. After the clear victory, Schroeder’s task is not easy: the search for reliable allies will require all his skills.